What is Wagashi?

Images courtesy of Premium Japan

Welcome to Madame Watanabe’s Japanese Culture Lecture Series.

Today’s theme is wagashi, traditional Japanese confections. I would like to offer a clear and accessible explanation for both Japanese and international audiences.

We will explore the history and varieties of wagashi, and reflect on why sweets made with mochi (glutinous rice) and an (sweet bean paste)—such as daifuku—have captured the hearts of people around the world in recent decades.

At this moment, I find myself deeply moved. Never did I imagine that the time would come when wagashi would be embraced by people who were not born and raised within the cultural sphere of East Asia.

I have an unforgettable memory. It was in the early 1980s. There was a TV program called ‘Yoru no Hit Studio, which was similar to the British music show ‘Top of the Pops’ on BBC1, featuring popular singers and bands. That night, a female group from the UK made a special appearance. On that day, a Japanese female idol singer who was also appearing on the show prepared handmade wagashi for them, and they were supposed to eat them on the spot.

In front of the TV, I had a very, very bad feeling. Unfortunately, my intuition was correct. As soon as they put the sweets in their mouths, they immediately spat them out. I do not blame them. They had no knowledge of this unfamiliar food or the cultural background behind it, so it was impossible for them to appreciate the taste of wagashi.

At least until the end of the 20th century, that is, until about 20 years ago, it was certain that people who came to Japan from Europe and America did not have a very good impression of the sticky texture of mochi and the idea of eating beans boiled with sugar as sweets, thinking it was weird.

In recent decades, Japanese ingredients such as yuzu (citron) and matcha (green tea), as well as the Japanese concept of umami (savory taste), have gradually spread into Western food culture. Finally, the sticky texture of mochi is no longer considered weird.

In other words, understanding this food culture requires a lot of accumulated experience.

Now, let’s quickly go through the history of wagashi and explain the different types of wagashi. I will also introduce some books that you can read in English.

History of Wagashi

The history of wagashi dates back to ancient times. Initially, it is assumed that they were very simple, made by grinding and combining nuts and other ingredients. During the Nara period (710-794), unique mochi and dango began to be made based on methods introduced from China. Subsequently, from the Heian period (794-1185) to the Muromachi period (1336-1573), the techniques evolved along with the court culture.

Sweets that came from China during this period are still being made today. A famous sweet from Odawara, Kanagawa Prefecture, called ‘Uiro,’ was created by Chen Yan You, who came from China in 1368, naturalized, and served the Japanese Emperor. It is a simple sweet made by steaming rice flour and brown sugar.

A major turning point occurred during the Muromachi period (1336-1573). With the development of the tea ceremony, there was a demand for delicate and beautiful wagashi to be served at tea gatherings, and the prototype of modern wagashi began to take shape.

Wagashi refers to traditional Japanese sweets. The term wagashi is derived from ‘wa‘, meaning Japanese, and ‘kashi‘, meaning sweets. In contrast, the term yogashi is used to refer to Western-style sweets. The Japanese distinguish between the two, with ‘yo‘ meaning Western.

Healthy Sweets Made Mainly from Mochi and Beans

There are two main ingredients used in wagashi: mochi and an or an-co.

Mochi is made from a type of rice called mochigome (glutinous rice). Compared to uruchimai (non-glutinous rice), which is used for regular meals, mochigome is much stickier. This stickiness is utilized to make mochi.

The traditional method of making mochi involves steaming mochigome (glutinous rice) and then pounding it in an usu (a stone mortar specifically for mochi) to shape it.

An (sweet bean paste) is made by boiling azuki beans until they become soft, then adding sugar and simmering for a long time until the moisture is gone.

Before simmering with sugar for a long time, it is necessary to soak the azuki beans in water and boil them. This pre-treatment is essential for making delicious an. It is a time-consuming process.

Sweets that Express the Four Seasons of Japan

Wagashi ranges from nerikiri (a type of wagashi served during tea ceremonies) to casual everyday sweets enjoyed by the general public. It is deeply connected to the seasons. Expressing the changes in nature and the four seasons is an important element.

In spring, wagashi are made to resemble cherry blossoms and fresh green leaves; in summer, they mimic cool waters; in autumn, they take the form of autumn leaves and chestnuts; and in winter, they are shaped like snowy landscapes and plum blossoms. These sweets visually express the changes of the seasons, allowing people to enjoy the unique flavors of each season.

Additionally, wagashi are indispensable for seasonal events and celebrations. Special wagashi are made for various occasions, adding color to these events. Now, let’s introduce wagashi for each season.

Spring

Sakura mochi (cherry blossom rice cakes), domyoji (a type of sakura mochi), and kusamochi (mugwort rice cakes) are representative of the Japanese Spring. These sweets are characterized by beautiful colors such as pink and green, which evoke the end of winter.

From the top left of the photo moving clockwise, you can see sakura mochi (cherry blossom rice cake) wrapped in a crepe-like pancake made from flour and filled with sweet bean paste; domyoji (a type of sakura mochi); sakura joyo manju (cherry blossom yam cake) topped with salted cherry blossom petals; and kusamochi (mugwort rice cake) made by steaming and finely chopping mugwort leaves.

Summer

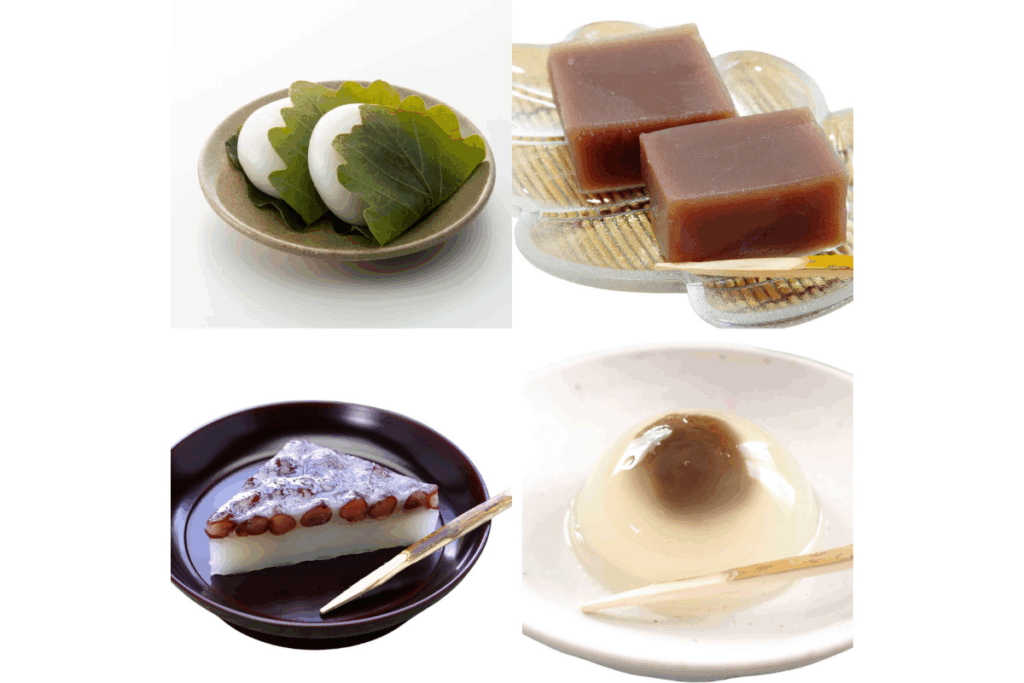

In early summer, starting with kashiwamochi (oak leaf rice cakes) eaten in May, there are many refreshing-looking wagashi such as mizuyokan (water yokan) and minazuki (a type of sweet made with rice flour and red beans) to help endure the hot summer.

From the top left of the photo, clockwise, you can see kashiwamochi eaten on the Boys’ Festival in May; chilled mizuyokan (soft adzuki-bean jelly), a summer wagashi; kuzumanju (kudzu dumplings) with a jelly-like texture that is perfect for summer; and minazuki cut into triangular pieces and topped with sweetened azuki beans.

Autumn

Kuri yokan (chestnut jelly) and kuri manju (chestnut buns) are popular wagashi made with chestnuts harvested in autumn. Additionally, there are tsukimi dango (moon-viewing dumplings) eaten on the night of the full moon in September, and ohagi (sweet rice balls) eaten during the Buddhist equinoctial week in September.

From the top left of the photo, clockwise, you can see kuri yokan (chestnut jelly) with plenty of chestnuts, kuri manju (chestnut buns) made by wrapping sweet bean paste and chestnuts in a wheat flour skin, ohagi (sweet rice balls) made by cooking glutinous rice, shaping it into a barrel shape, and wrapping it with sweet bean paste, and tsukimi dango (moon-viewing dumplings) eaten on the night of the full moon in September.

Winter

Hanabira mochi (flower petal rice cakes), which are served at New Year’s celebrations and the first tea ceremony of the year, uguisu mochi (nightingale rice cakes) that mimic the bird heralding spring, and plum-shaped sweets that emit a sweet fragrance even in the harsh winter are all winter wagashi. Additionally, at home, people enjoy oshiruko (sweet red bean soup) made with leftover mochi from New Year’s.

From the top left of the photo and going clockwise, you can see hanabira mochi (flower petal rice cakes) eaten during New Year’s celebrations, uguisu mochi (nightingale rice cakes) made by wrapping sweet bean paste in gyuhi (a type of soft mochi) and dusting it with green soybean flour, oshiruko (sweet red bean soup) and nerikiri (a type of wagashi) beautifully shaped like plum blossoms.

Variety of Types

There are many different types of wagashi. Here, let’s introduce some popular wagashi that can be enjoyed all year round.

Daifuku, ohagi and dango are popular wagashi enjoyed by the general public, while nerikiri is often served during tea ceremonies. Additionally, monaka, rakugan and castella are also considered types of wagashi.

Nerikiri

Nerikiri is a beautifully crafted sweet often served during tea ceremonies. It is made by carving beautiful designs into a base of shiroan (white bean paste). Although it has a texture similar to mochi, it is made with gyuhi. Gyuhi is made by kneading powdered mochigome (glutinous rice) with sugar and starch syrup. It is softer and smoother than mochi.

Nerikiri is a type of wagashi that beautifully expresses seasonal plants, animals and natural scenery.

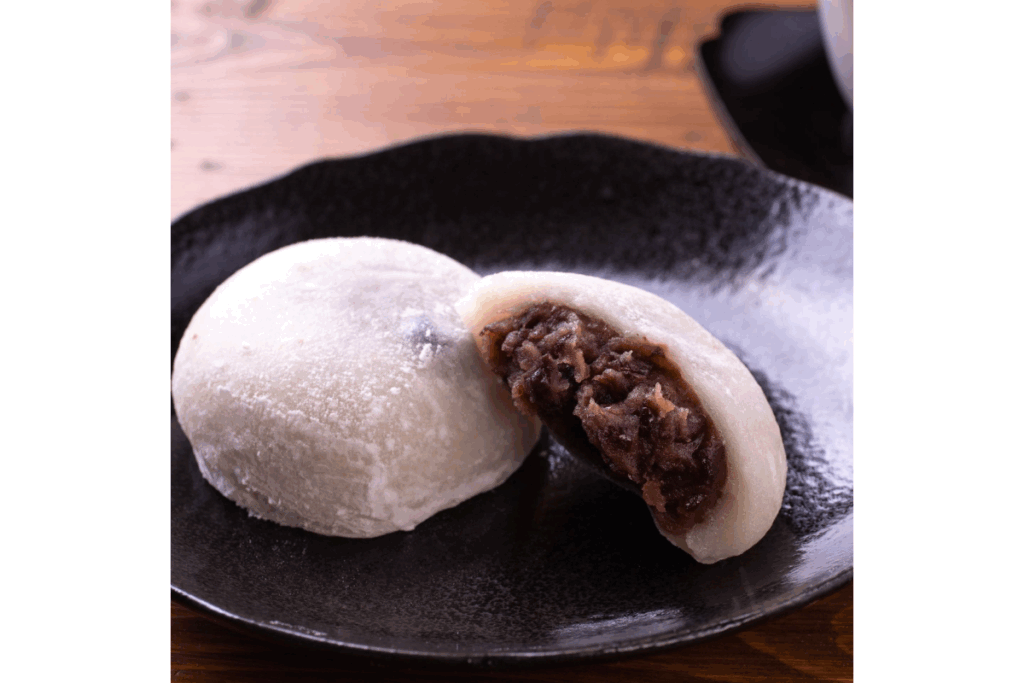

Daifuku

Daifuku is made by powdering dried mochigome, mixing it with sugar, and then stretching it to wrap the sweet bean paste. The mochi or crackers that wrap the sweet bean paste are called kawa (skin) by Japanese people. Daifuku is enjoyed all year round.

Daifuku is becoming a popular sweet overseas as well. About 40 years ago, a new type of daifuku was invented, which included a whole fresh strawberry inside the sweet bean paste. The sweetness of the bean paste matched perfectly with the tartness of the strawberry, and it quickly spread nationwide. Nowadays, fruit daifuku made with various fruits such as grapes and mangoes are also gaining popularity.

Ohagi

This wagashi is made by cooking a mixture of glutinous rice and non-glutinous rice, shaping it into small balls and then wrapping them with sweet bean paste to form the shape. Besides sweet bean paste, there are also variations that are coated with kinako (roasted soybean flour mixed with sugar).

Ohagi is enjoyed all year round, but it is especially eaten during the two equinoctial weeks in spring and autumn when people visit graves.

Monaka

Made by placing sweet bean paste between thin, wafer-like crackers, monaka are prepared by baking thinly stretched mochigome flour. You can enjoy the crispy texture of the crackers and the sweetness of the an. Recently, fine dining chefs have been incorporating monaka crackers into their dishes.

The crispy texture of the crackers and the sweetness of the an are a perfect match. Try it with Japanese tea or roasted green tea.

Dorayaki

This wagashi is made by mixing ingredients such as flour, eggs and sugar, and baking them into two round pancakes with sweet bean paste sandwiched between them. The fluffy pancakes match perfectly with the sweet bean paste, making it a classic souvenir sweet in Japan. Madame Watanabe’s favorite is the dorayaki from Kameju in Asakusa (浅草 亀十).

Castella

A confection made by mixing eggs, sugar, starch syrup and flour, and then baking it in an oven, castella was introduced to Japan by the Portuguese 400 years ago. There is a theory that when the Japanese asked the Portuguese for the name of this confection, they replied ‘Bolo de Castela’ (a confection from the Kingdom of Castile [present-day Spain]), which the Japanese misunderstood as the name of the confection.

Wagashi is a condensed expression of Japanese aesthetics. Additionally, they are very healthy as they do not use fats such as butter and are low in calories, making them a perfect match for modern times.

Since you can find daifuku and yokan at convenience stores, trying various types is the quickest way to get to know wagashi (don’t underestimate the quality of recent convenience store sweets).

Guide to Understanding Wagashi

Let me introduce two books about wagashi that you can read in English. I think you will enjoy them along with the beautiful visuals.

This is a photo book featuring wagashi from long-established Kyoto wagashi shops, Kawabata Douki and Kameya Iori, beautifully captured in photographs and accompanied by the words of poet Mutsuo Takahashi. It is a bilingual coffee table book in Japanese and English, perfect for leisurely viewing at home while admiring the beautiful photos. Published by PIE International.

This book explains 50 types of wagashi familiar to Japanese people’s daily lives with watercolor illustrations and English text. It covers everything from ingredients and methods to history and was published by Seibundo Shinkosha.