Crime at a Crossroads: The New Response Dynamics

Organized crime thrives worldwide. It operates across borders, exploits vulnerable people and undermines global security. As the world faces significant challenges from violent conflicts, climate change and the rise of AI, organized crime cuts across all issues.

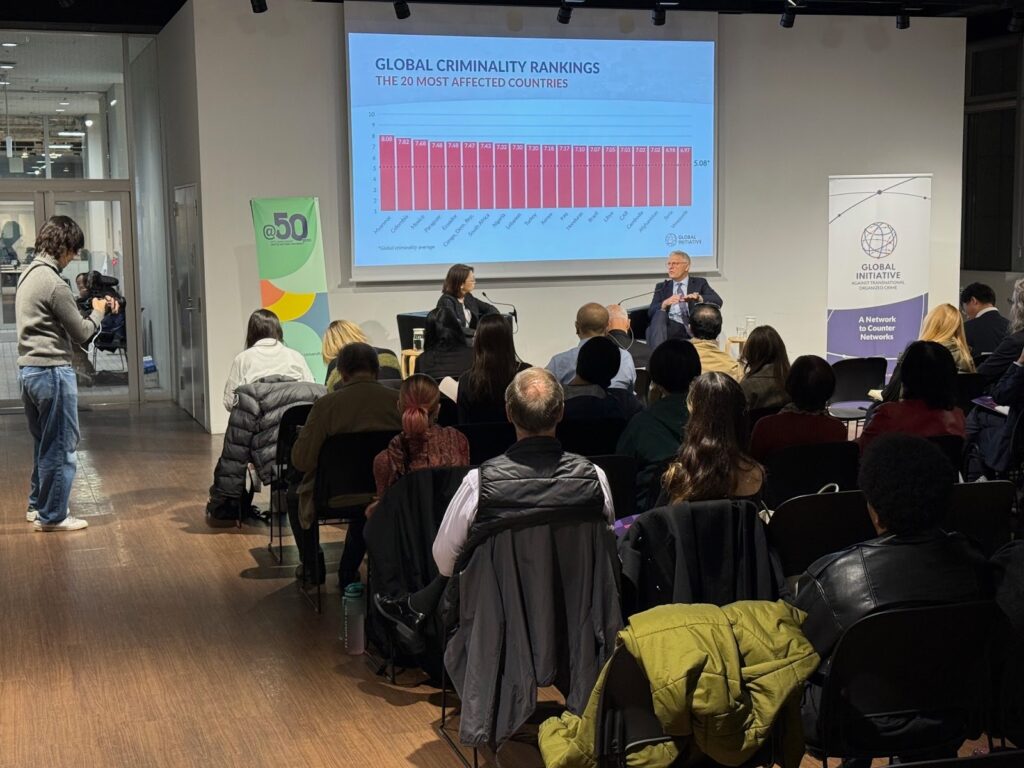

That was the intro to an event featuring Dr Mark Shaw, executive director of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. He appeared at the United Nations University in Tokyo on November 11 to present the latest edition of the Global Organized Crime Index, which revealed how and where criminality is evolving today.

The third edition of the bi-annual index includes data on criminality and resilience against organized crime for all 193 UN member states. It aims to demonstrate how organized crime and resilience have evolved over the last four years since the first index was released. Dr Shaw explained why Japan is a good example of how the criminal justice system should tackle organized crime.

“The world is at a crossroads when it comes to dealing with illicit economies. Organized crime is undermining democracy, the sovereignty of states and even international peace and security. The rules-based order that has prevailed for decades is now being exploited by those who don’t play by the rules. Criminal groups are some of the biggest profiteers,” he said.

Illicit economies reflect broader socio-economic, political and geopolitical processes, because criminals are often the ones who adapt first and take advantage of disruptions such as geopolitical competition, rapid technological innovation, violent conflicts, trade wars and the erosion of democracy. So, the Global Organized Crime Index is not just a tool for measuring crime: it is a mirror reflecting what is going on within states and the international system.

“Since this is our third edition, we now have three data sets that enable us to track and compare how criminal markets and actors have evolved over the past five years.”

Among the findings, the data of this edition of the index identifies that there have been several shifts in the global criminal economy. For example, synthetic drugs and cocaine are rapidly dominating world drug markets. This shows the ability of criminal actors to capitalize on changing consumer preferences, technological developments in production and increasingly interconnected trafficking networks.

At the same time, this index shows a significant and rapidly growing trend: a rise in non-violent forms of crime such as financial and cyber-dependent crimes. These “invisible” forms of organized crime are less reliant on traditional violent methods or corruption, but have become more embedded in transnational financial and digital systems. They are often harder to detect. Despite the absence of violence in these illicit economies, they still cause untold harm. Financial fraud and cyber-dependent crimes have high costs for their victims—individuals, businesses and states.

Counterfeiting, another silent crime, is also becoming more pervasive, the index finds. Inflation, weak economies, job insecurity and trade wars are fuelling this market as consumers with less purchasing power seek cheaper products.

This year’s index also shows that, while state-embedded actors are the most prevalent criminal actors, yet again, foreign actors registered the sharpest overall increase since the last index in 2023. This suggests criminal groups are increasingly mobile and that there is closer transnational cooperation between them. Private sector actors are also playing an increasingly significant role in illicit economies, particularly as facilitators of criminal activity, for example in logistics, finance and technology.

In addition to analyzing criminal markets and actors, the index measures resilience. While many criminal markets are witnessing growth, resilience scores appear to have plateaued. An example of this is international cooperation. While this indicator usually outperforms the other 11 resilience indicators, an increasingly fractured international system and a retreat from multilateralism suggest that states are less willing to cooperate to fight crime.

That said, the trajectories of crime can be changed. For example, the index shows that statistically, by strengthening key areas of resilience, we can reduce the influence of state-embedded actors over illicit activities to a measurable degree, while stronger response measures can shift communities, even societies, into a more positive direction.

Dr Shaw, a South African, is a widely recognized expert on global organized crime and illicit markets. He used to be the National Research Foundation Professor of Justice and Security at the University of Cape Town, Centre of Criminology. He worked for 10 years at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, including as Inter-regional Advisor, Chief of the Criminal Justice Reform Unit and with the Global Programme against Transnational Organized Crime, with extensive field work. He is also a Board Member of the European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control (affiliated with the United Nations), in Helsinki.

“With all forms of organized crime shifting online, its reach and capability of harm is increasing. In recognition of these shifts, there is an urgent need for further research on organized crime to understand these changing criminal markets and ecosystems. Most importantly, pioneering innovative strategies to tackle these issues are at the heart of progress on international peace and security.”

He was joined on stage by United Nations University (UNU) Senior Vice-Rector Prof. Aya Suzuki to discuss building strong, resilient responses to organized crime. As organized crime evolves across borders and becomes increasingly digitized, how can countries share leadership and responsibility to ensure collective security? How have technological innovations, including the advancement of AI, changed patterns of crime? What leadership role can Japan play in responding to global organized crime?

Dr Shaw said, “There are 15 criminal markets, led by financial crime, followed by human trafficking, the cannabis trade, arms smuggling and synthetic drugs, especially in Southeast Asia. Organized crime is growing and four of these crime types have grown in the two years since the last report was published. Organized crime has become cyber-dependent and is strengthened by its foreign actors.”

He showed the audience slides that revealed the list of the top 15 crime-ridden nations led by Myanmar, Latin America and Africa. Nations are measured by criminality and resilience. “Japan has high resilience and low criminality thanks mainly to the smaller numbers of Yakuza gangsters these days, caused by effective policing and anti-gang legislation.” Singapore and South Korea also score low on the vulnerable index.

Technology is making it easier for drones and cyber scams to operate, but the digital revolution also helps police. “AI is an effective tool for law enforcement, but the data put into AI must be accurate to start with and that’s where some countries are being left behind. Japan has the capacity to respond to criminality, but some poorer nations with fewer resources suffer serious problems with organized crime,” said Dr Shaw, who added that scam crimes are much harder for police to solve if they are carried out abroad. “It is not easy to increase resilience. Democracies are more resilient and it is more difficult to hide crimes where the law is enforced with integrity and political leadership.”

Issues-based activism can bring about change if it involves behind-the-scenes efforts such as lobbying lawmakers, global teamwork and community support. The goal is to raise public awareness and advocate for policy or legal changes related to the identified issue. A great example is piracy; a coalition of states has practically ended attacks by pirates around Somalia and in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean. “But new players are coming in and dynamics are changing. Nations such as Myanmar and the Democratic Republic of Congo need large amounts of quick cash to fund war and instability.”

What can we do? “Japan can play an important role such as it did over the past 20 years in response to the Yakuza threat; this was enormous, much more than Japan realizes.”

“We are soon going to publish a crime report on Ukraine, but both Ukraine and Russia have huge organised crime networks.”

Can banning cash help? “Restricting cash is good crime prevention as it introduces taxes and accountability. Many global crime statistics are actually declining at a national level, so people are asking what the problem is. The problem is that statistics are not always an accurate reflection; we must attempt to bridge that gap.”

And contrary to popular belief, most victims are poor, not the middle class. “The biggest concern in the poor nations of Southeast Asia, for example, is not education or jobs, it’s crime. Scam centers break down state stability, so we must sanction leaders, elect fewer populist leaders, educate the people and apply political pressure to act together and fight scams.”